Material progress could be measured by such yardsticks and life expectancy, average health of the people, and better living conditions in tangible terms such as housing and the ability to cope with natural disasters. On a cultural level, progress includes literary and artistic creation, scientific and technological discoveries, participative politics and the rule of law.

But is it possible to question the very existence of a curve indicating linear progress? Isn’t it possible that human history proceeds in zigzags with “lower” and “higher” points alternating according to mysterious laws?

Applied to the “Muslim World”, the theory of progress hardly resists the challenge of the rival theory of historic zigzag.

At material level, progress made by virtually all Muslim-majority countries in the past 100 years is amazing.

A century ago, Muslims accounted for less than four per cent of the world population. In 2017, that has risen to almost 25 per cent. Muslims have also benefited from progress in life expectancy, public health and material living standards beyond their wildest dreams even a century ago.

I remember how as a young reporter in 1970, I fell into depression after a visit to what was then East Pakistan. I had not imagined so much human misery in my worst nightmares.

Half a century later, Bangladesh, the state that emerged from East Pakistan, is still poor by most standards but, when it comes to absolute poverty, is no longer the hell-hole it was in 1970; it has benefited from economic development and material progress.

On a grander scale, I remember the Trucial States, which were to become the United Arab Emirates. Outside Dubai, which had one hotel-like establishment, none had any proper facilities. In the Sultanate of Oman, we had to bivouac in private homes with no electricity and/or running water, and eat boiled goat and half-cooked rice. Now, of course, both the UAE and Oman boast some of the most luxurious tourist establishments in the world.

Similar observations could be made about almost all other Muslim countries, including my own homeland of Iran, which began to emerge from medieval poverty only in the 1960s.

In 1973, Tehran hosted a conference on “modernization”, co-sponsored by a United Nations agency in charge of Asia. The consensus was that material progress will lead to cultural and, eventually, political progress.

Six years later, Iran had fallen under a clerical tyranny built around a hodgepodge of pseudo-religious mumbo-jumbo and half-baked Marxist-Leninist methods. Suddenly, even classical Persian poets were censored or, in some cases, banned. Worse still, the Khomeinist sect that held power arrogated to itself the right to issue anathemas and interdicts, inventing its versions of the Inquisition and Excommunication, mechanisms that do not exist in Islam.

In 1960, when I arrived in Britain to go to school, I was surprised to find out that the Lord Chancellor had a blacklist of banned books at a time that no such abomination existed in Iran. Less than two decades later, there no longer was such a blacklist in the UK, while the Islamic Republic in Iran had worked out the longest blacklist in human history.

Even worse, the Khomeinist sect claims that anyone who does not blindly obey the current “Supreme Guide” is an “infidel”. Of course, the incumbent himself is not immune against such anathema. One day, he, too, could be hit with the “mace of takfir,” as he has happened to many leading figures of the Khomeinist regime, including four of the Islamic Republic’s six presidents.

We need to go back to history to see how the zigzag works.

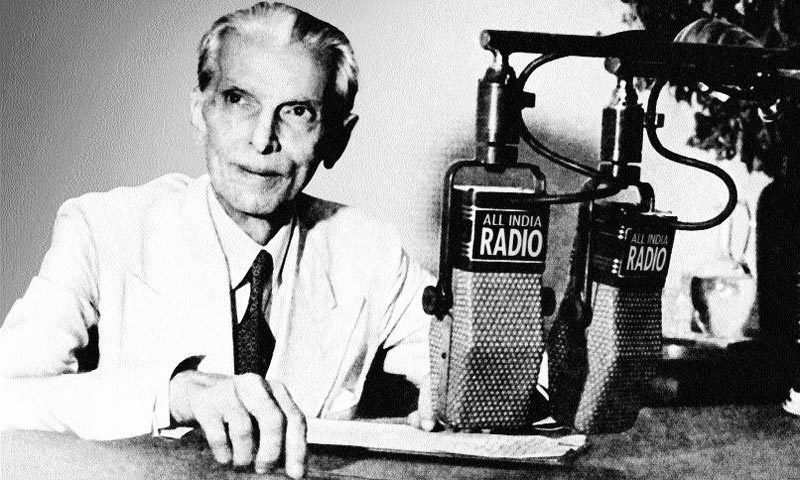

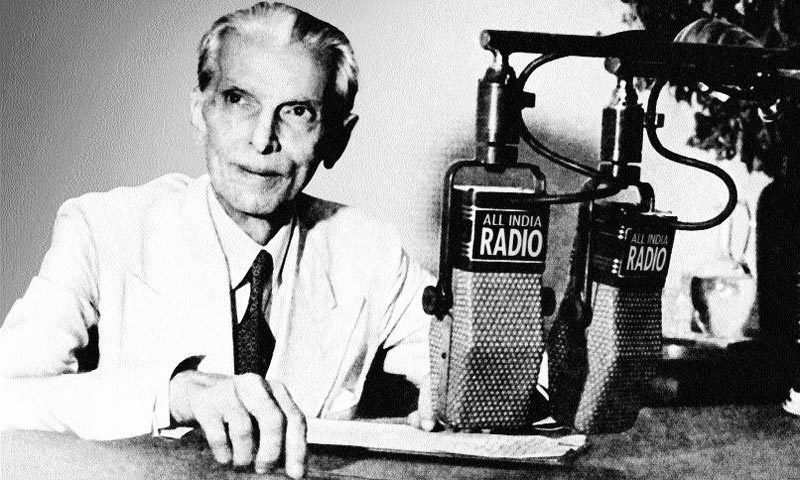

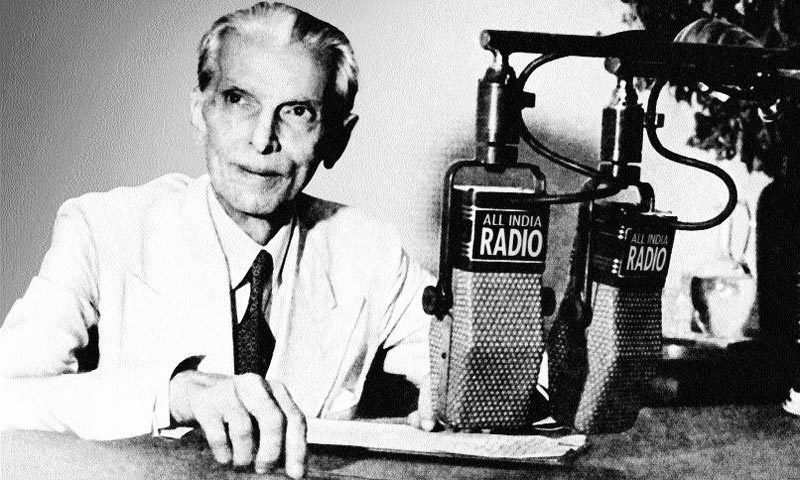

Muhammad Zafarullah Khan, Pakistan’s second foreign minister, belonged to the Ahmadi minority, and even served as their Ameer (religious leader) for a while. And, yet, his religious affiliation never became an issue. Today, however, Ahmadis are hunted and murdered by neo-Islamist militants not only in Pakistan, but also in Britain. No one in Pakistan cared that the “Father of the Nation,” Muhammad Ali Jinnah, was a secular politician. Today, the label secular could get you killed.

|

In Iran under the Shahs, building a political career did not hit sectarian hurdles, and Sunni Muslims held high offices as ministers, governors, ambassadors and military commanders. (The Minister of Justice in the last cabinet formed under the Shah was a Sunni Muslim lawyer.)

Today, however, only one Iranian Sunni Muslim holds a high post, as Ambassador to Vietnam, a country with limited relations with Iran.

In Indonesia, which has the world’s largest number of Muslims after India, such reformers as Abdul-Rahman Waheed and Nucholish Madjid enjoyed wide audiences and enough freedom, even under the military dictatorship, to promote their views in the marketplace of ideas. Today, many of their works are banned and seminars on them are attacked by neo-Islamist militants who claim they can decide who is a Muslim and who is not.

In Turkey, the neo-Ottoman elite won’t even allow former Islamist allies, led by Fethullah Gulen, even a tiny space for dissent.

And what about the mass murder of over 300 Egyptian adepts of Sufism at a mosque in the Sinai last week? Yes, Egypt, which throughout Islamic history was a cradle of Sufism and the birthplace of “alternative” ways of understanding and living Islam? “Egypt, where the perfume of a hundred flowers refreshes the believer’s soul” said the great Persian Sufi poet Sanai.

Almost 1,000 years later, there are people in Egypt who do not tolerate even a single flower, insisting that their violent thorn should conquer the earth. Had the Enlightenment theory of progress been right, today in Egypt we would have a thousand flowers instead of a single blood-stained thorn.

Today, we are wealthier, better educated and healthier than ever in Islamic history. And yet, we are faced with more ignorance, prejudice, fanaticism and violence than ever.

Others now remember us when they are asked to take off their shoes at airports and when they see our self-styled extremists cut people’s throats on television.

So, maybe we are in a zigzag mode. If so, the question is how to zig our way out of the current deadly zag?

______________

Amir Taheri, formerly editor of Iran’s premier newspaper, Kayhan, before the Iranian revolution of 1979, is a prominent author based on Europe. He is the Chairman of Gatestone Europe.

https://www.gatestoneinstitute.org/11476/progress-history